Séverine Lambour and Benoît Springer invite you to follow Claude Gueux in the hell ofnineteenth-centuryprisons. Beware because the shadow of the guillotine is close in this adaptation of Victor Hugo's novel at Delcourt.

Claude Gueux based on real events

Claude Gueux was initially a charge of the author of Les Misérables published in 1834 against the death penalty and the prison system that crushed beings rather than allowing them to reintegrate. Hugo was inspired by real events to describe Claude's tragic fate. This honest worker driven by poverty had to steal bread to feed his family. With no support, he was sentenced to prison. In the jails of Clairvaux, Claude submits to the slightest rule. In addition, because of the gentleness of his character, he is respected by the other inmates and befriends one of them, Albin. But the director does not intend to let these two men have influence and separates them. To survive, you have to have outside help that brings in food. Claude always remains dignified while the director abuses his power to maintain absolute control over the men. The script captures very well this opposition between a ruthless elite and a mass of victims always in solidarity. It can be seen as a criticism of the prison system but also a denunciation of the monarchy and an ode to the people. Like an ancient myth, the tension slowly but inexorably rises until the final drama that tears your heart.

A dive into the past

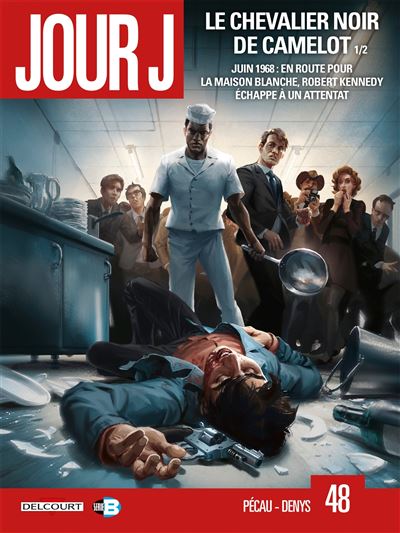

The first pages show the misery of the time by sparing dialogues. While Paris shivered under the snow, Claude had nothing to eat, his seamstress wife could not find any tasks and their only daughter was cold. His father will help them survive for a while but the drama catches up with them all. Claude Gueux does not even try to flee the police who knock on the door as soon as the theft is committed. The heavy atmosphere is set from the superb cover divided in two between the power of the prison system embodied by the director of the prison of Clairveaux at the top and the collapse of a simple man, Claude. The cartoonist Benoît Springer recreates well the peculiarities of prisons at the time – vast collective cells in a former monastery – and makes us live, among the prisoners, a difficult life: no toilets, insufficient and monotonous meals. By the subtle repetition of an identical box on several pages but with different colors, the artist shows the monotony and the passing of the seasons. His modern line combines the precision of bodies and decorations with a very powerful expressiveness of faces. The large format of the book does justice to these large boxes full of humanity.

A load that is still relevant today

Of course, we may think that this era is over, but current events have shown that people are still driven to theft by hunger. Prisoners also have uniforms. As today, they are reduced to the state of silent robots which shows very well the few dialogues with a very reduced vocabulary. Séverine Lambour also makes the very judicious choice of the unsaid. There is no recitative and she cuts a large part of Hugo's text to keep only powerful dialogues or let the atmosphere settle. Social inequality and the solidarity of the excluded are still the tragedy and salvation of our time. The friendship between the inmates seems to us almost a love story prevented. Claude Gueux is a magnificent adaptation of Victor Hugo's text. By the very bold choice not to use the original text, the story is even heavier and merciless. The accurate and splendidly expressive drawing makes the protagonists of the drama terribly human. You will not remain insensitive to the text in the last box and once this comic is finished, it is very likely that you will run to find Hugo's novel to check if the words are as strong as these images. If you are interested in writers of the past, we recommend this column on the biography of George Sand or Sheridan Manor set at the same time.

Of course, we may think that this era is over, but current events have shown that people are still driven to theft by hunger. Prisoners also have uniforms. As today, they are reduced to the state of silent robots which shows very well the few dialogues with a very reduced vocabulary. Séverine Lambour also makes the very judicious choice of the unsaid. There is no recitative and she cuts a large part of Hugo's text to keep only powerful dialogues or let the atmosphere settle. Social inequality and the solidarity of the excluded are still the tragedy and salvation of our time. The friendship between the inmates seems to us almost a love story prevented. Claude Gueux is a magnificent adaptation of Victor Hugo's text. By the very bold choice not to use the original text, the story is even heavier and merciless. The accurate and splendidly expressive drawing makes the protagonists of the drama terribly human. You will not remain insensitive to the text in the last box and once this comic is finished, it is very likely that you will run to find Hugo's novel to check if the words are as strong as these images. If you are interested in writers of the past, we recommend this column on the biography of George Sand or Sheridan Manor set at the same time.