After the revolt of May 1968, revolutionaries wanted to engage in the world of work as shown in this biography published by La Boîte à Bulles. Fabienne Lauret recounts her life as a worker and revolutionary feminist activist. Enter through this chronicle into the unknown world of the factory.

A James bond in working blue…

While reading Fabienne Lauret's biography, Guillaume was moved by the author's sincerity, the strength of feminist convictions and the fidelity of revolutionary commitment. Unlike his previous books on finance, he reduced the fiction part to get closer to the testimony.

In the first pages, Fabienne is an active retiree in Flins who does yoga and talks to sheep. Yes, you read that right. It is by passing in front of the sheep used to maintain the lawn of her old factory that the author begins her story. These ruminants were for her a parable of the powerless workers, their diversity and their gradual disappearance. But how did she get into the factory? His life changed in May 1968. This revolt marked his political awakening materialized by his adherence to the revolutionary communist youth. It chooses to establish itself, that is to say, to integrate into a factory. It does not come to earn a living but in order to make the revolution of the proletariat triumph.

The entry of revolutionaries into these factories is worthy of a spy novel. A secret group formed around Flins. Highly motivated activists find a base and take risks, as evidenced by death threats they receive. Fabienne has a pseudonym and then creates a past as a worker. She is an excluded among the excluded because she is a revolutionary feminist while there are only 10% women in the factory. At the same time, she became a delegate to the CFDT and was also a feminist activist outside the factory.

… in an unknown world

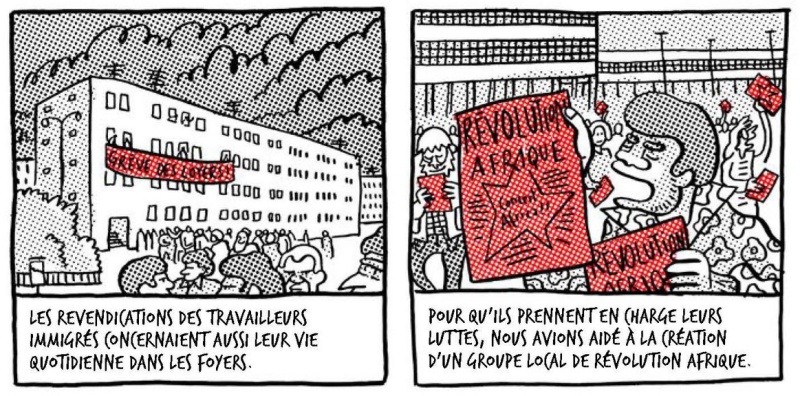

The reader of A Revolutionary Feminist in the Workshop enters another world. On the one hand, the culture shows little of the workers as if we did not want to see them. On the other hand, the media never ceases to prophesy the disappearance of the workers. Moreover, the Flins plant has grown from 21,000 to 5,000 employees. Fabienne's experience is a revelation for the reader. You can feel the effects of the plant on the bodies. The wear is done by the repetition of the same gesture. The worker must not think but carry out the tasks as quickly as possible. Immigrants are the perfect workforce because they are less politicized and low in literacy.

But, we can also see collective struggle and individual resistance. We understand how a social conflict starts in one workshop and spreads to other factories. We are frightened by the violent reactions of the management. The shop steward is in a balancing act by having to be careful not to be too detached from their reality. Naturally, there is solidarity between the new workers and the more experienced. The infirmary is a valve to escape the infernal cadences. However, the factory is not united. The all-male press workshop is harder but also more committed than the upholstery.

The cartoonist Elena Vieillard makes this political story very intimate. She is herself an activist and a member of the Vulves assassines, a feminist punk-rap group. His line is more symbolic than realistic. Vieillard does not aim for precision but emotion by drawings close to cartoons or caricature. She was inspired by archive images of workers' movements and Fabienne's personal documents but also by her childhood memories because she lived near Billancourt. Vieillard chooses duotone and obviously red to emphasize the emotion of the struggle and anger.

A revolutionary feminist at the workshop gives the impression of traveling to another century. This is collectively the case by the highly hierarchical relationships in the factory and individually by Fabienne's revolutionary feminist commitment. We can clearly see from the very dense documentary file at the end that Fabienne continues the struggle.

Find on the site other chronicles of life with La France vue par madame Hibou and L'enfant des rivières.