Leave, the watchword of Ibn Battuta

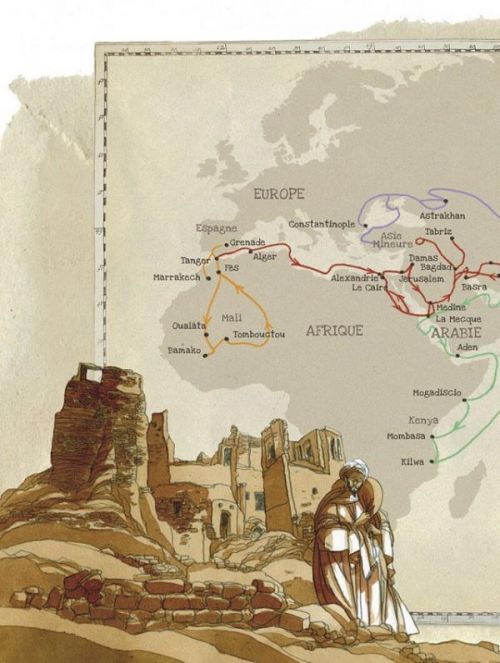

At a time when the world, in the grip of a pandemic, is cloistered and no longer touching, the "Aire Libre" collection invites us to "shut ourselves outside" with the story of the travels of the legendary Muslim figure of Ibn Battuta, a Tangier explorer still too little mentioned in France. It is the writer Lofti Akalay, intrigued by the little-recognized figure of Ibn Battuta, who sets the tone and smiles at Joël Alessandra's watercolors. This collaboration paves the way for seven years of research and hard work on our explorer, who traveled 120,000 kilometers between 1325 and 1349, visiting 48 countries. Released in June 2020, this comic book proposes to create a travel diary with shimmering colors, mixed with travel anecdotes and the story of a man traveling "terra marique", the Islamic world, in order to get closer to God.

An adventure of disputed veracity

The straight paved roads put off Ibn Battuta. Born in Tangier in 1304, a lawyer by training, he left at the age of 21 to make his pilgrimage to Mecca. He returned to Morocco, to Fez, twenty-nine years later. His memoirs were compiled by the scribe Ibn Juzayy al-Kalbi. Originally wanting to perform his hajj, Ibn Battuta realized how easy it was to explore Islamic lands, connected by new trade routes. From caravan to caravan, it joins the trading posts of China via Asia Minor, the Persian Gulf, India and Sumatra. The itinerary of this explorer is very vast, he is driven by a desire to discover the Muslim lands and to bring back sketches and anecdotes. If Ibn Battuta is not as recognized as Ibn Khaldun (precursor of sociology, intellectual, 1332-1406) and Ibn Jubair (intellectual at the court of Al-Andalus, 1145-1217), it is because he does not claim to be an intellectual or historian. He proposes to share what he sees and especially the anecdotes that the natives tell him. As a result, it does not support facts but is intended to integrate the reader into his journey and make him a companion on the road.

Ali Benmakhlouf, professor at the University of Paris-Est Créteil and senior member of the University Institute of France, takes care in the preface to recall that the story of Ibn Battûta is authentic in that it does not ring false. Therefore, it is necessary to explore his work and to dispel the prejudices making him a fabulator. Ibn Battuta did make this vast journey but his approach is not didactic. On the contrary, it seems that he wishes to follow the theme of the "invitation to travel" and emphasizes an understanding of the world through experience. This empirical approach reminds us of the Rousseauist conception of knowledge in the Reveries of the Solitary Walker. Knowledge is made on the basis of spontaneous discovery, contemplation of the world. In the seventh walk, Rousseau recounts the episode of herbalization. When he walks in nature, he ignores the Latin terms for plants and simply relearns how to discover them. Nature has been alienated by a rigorous and scientific classification, but when we approach it without knowing its Latin name, it produces on us the effect of a reverie, of an escape from the world. Rousseau finds refuge in a nature that he rediscovers, she "charms" and "amuses" him in his own words. As a result, Ibn Battuta's poetic production is based on the account of a journey that is based on the innocent discovery of the world, although he praises the Muslim world in passing.

Travel, a sought-after isotopy

When Ibn Battuta reached Timbuktu, the reader could not help but think of Major Alexander Gordon Laing and René Caillié. The second returns alive from this city to the mysteries, the first having been murdered when the natives discovered the deception (the city is forbidden to Christians). Because in reality, the story of Ibn Battuta enters into connivance with a sought after orientalism and still relevant in the West. The desire for somewhere else is still alive, indeed. The face of this Berber woman who haunts the dreams of Ibn Battûta can only remind us of Pierre Benoit's Atlantis (1917) when Morhange and Saint-Avit hear thanks to the Tuaregs about the legend of Antinéa, in the Saharan desert. Knowing very little about the Muslim world, our explorer, like the Traveler contemplating a sea of clouds (Caspar Friedrich, 1818), goes in search of the romantic volutes that would lead him to the Ideal. As he travels, Ibn Battuta sharpens his pen and improves his stroke. As he travels, he becomes aware of the inanity of human life in the face of the greatness of nature. And as he travels, Ibn Battuta again encounters the sublime. This aesthetic is highlighted by the dangers that the explorer crosses, between shipwrecks, diseases and robber attacks. His quest oscillates between the desire for survival and the instinct for death, since none of our explorer's misadventures cuts off his obsession with the road. On the contrary, knowing that he was protected by God, Ibn Battûta attested to his baraka by bringing back to the Sultan of Fez, at the end of his journey, a trunk filled with drawings.

Ibn Battûta, in the pantheon of travelling poet princes?

In the continuation of a series of "rehabilitation" (like Jeanne Duval), the current comic strip proposes to explore the lives of the vanquished, those who were not justly recognized during their lifetime. Ibn Battuta does not flee from fire or injustice (such as the scene where he distances himself from the Indian tyrant who tortures a high dignitary prisoner), certainly driven by his faith, but especially by the reckless instinct of the traveler forged in all the latitudes of this world. He makes his honey of the anecdotes that he weaves in his work to make a new imagery, revealing both the beauties and the ugliness of the lands he trods. Between sabre blows and beautiful women, the work of Ibn Battûta is reminiscent of the odysseys of Rimbaud or Corto Maltese. He feels the need to leave to check memories, to reconnect with the Lord, to go away "with his fists in my pockets punctured". He makes fun of the superstitions and lack of rationality of the peoples he meets: Ibn Battuta knows that the dream is golden, poetry queen, and that reality is bitter. This is what he would have to answer to Ibn Khaldoun's accusations. He tries to find a dream, and this materializes when he finds the woman of his dreams, in Morocco, at the end of the album. Ibn Battuta seems decidedly to belong to the Wanderers, poets and shamans, to those who dive into all the waters of the globe. His unprecedented journey recalls that of Charles de Foucauld, first explorer of Morocco at the end of the nineteenth century, since pushed by their faith (despite different religions, one Christian and the other Muslim), they give birth to a new promised land for mystics. Therefore, Ibn Battuta proves that the nation of poets knows no temporal or religious boundaries. The only condition for integrating it is this quote from Nietzsche from Thus Spoke Zarathustra: "Of all that is written, I love only what one writes with one's own blood. Write with blood and you will learn that blood is spirit."