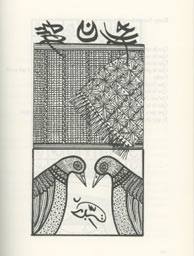

From an iron chisel – twenty years of committed Israeli poetry (Al Manar editions), this is the undertaking in which the Israeli poet Tal Nitzán has invested: an anthology, translated into France in 2014, bringing together poems from 1984 to 2004, accompanied by drawings by Rachid Koraïchi, to describe an unacceptable reality that the artist – draftsman or poet – sets fire to by his testimony. In fact, the aim of the project is to denounce the abuses committed in their country against the Palestinian people.

From an iron chisel: the poet's commitment

We tend to perceive the poet as the Mallarmén man, reclusive in his tower, far from ordinary mortals. This representation is a distorted image, contaminated by nineteenth-century romanticism. Instead, Tal Nitzán presents us with a panel of authors, sometimes angry, sometimes sad – often both – who refuse to remain distant from the world : on the contrary, they register with strength and affirmation. Take as an example the second poem of the anthology, by Rami Dizani, Mourning the beloved country beginning with "I cry because my people have no heart to cry". How then can we not think of Césaire and his Cahier d'un retour au pays natal which sings of this "city missed by his cry"? This is the poet: the creator who gives his voice to those who do not have it, or no longer.

The responsibility to make your voice heard

The poet as an educator of crowds, of what Rami Dizani calls a "pre-nation" because "nation devoid of brother-men, unity, compassion, devoid of human love". In his poem, and in those of many others in the collection, he says his shame, that of a man in the face of trivialized violence, the loss of identity, the indifference of men among themselves, who continue their lives, for whatever reason:

[…] I did everything I could to keep going

in the scheme of things,

But in the evening, the television off, I saw her

climbing, wheezing,

[…] the crack that forms

[…] whereas

We continue.

Arik A. Palestine-Eretz Israel

Yet all these poets say something other than despair and renunciation. Their voice carries within it the seeds of refusal, the refusal to consider men as already dead, the refusal to have to renounce their voice, the refusal of self-denial to the violence and injustice of everyday life.

Word of the poet: I have no choice,

even if all this is the product

of the regime – the history of poetry

as well as borders

talking – I have no choice,

I must oppose

Yitzhak Laor, Veal

From an iron chisel: a polyphonic work

Itis therefore an enterprise with several voices, which interact and participate in a common discourse, that of the right of peoples to live in peace. Poetry in prose (Rami Dizani, I am Purim), in free verse (Dahlia Rabikovitz, Our captors order us to sing), fragmentary (Tuvia Rubner), or on the contrary amplified (Tamir Grinberg, Praise), men or women, all poets above all else.

It is therefore a song of love that unfolds through these pages, a song that I felt it was important to share, in an era where walls replace exchanges, where people are rejected from their country, martyred, and where the stranger becomes a source of fear and rejection. In such a case, the voice of the poet is primordial, it reminds us of ourselves, of what is human in each of us, and pushes us to seek this common root of humanity in the other.

Fatigue with a high head

We have grown dust in our bodies

But what connects us here could

still be repaired in this place.

Asher Reich, Under the Olive Tree

Article written by Julie Madiot