Predator and prey: the scheme is simple, but the challenge is enormous. The prey could have been Cormac McCarthy's novel, which the cinema would have dissolved indigestibly in a style seen and reviewed, as it has already done hundreds of times by adapting literary works. But the Coen Brothers seized No Country for Old Men, and made it a major work of cinema and an adaptation as we have rarely seen. To (re)watch on Netflix now.

The Coen Brothers never tire of reinventing the rules of cinema: after the excellent Fargo and The Big Lebowski, here they are back with No Country for Old Men in 2007, a thriller with western flavors. But here, no more sheriff enforcing his law, or narrative diagram well written and followed to the letter. Here, violence and disobedience are in the spotlight. We kill with ease, we save by chance, all lulled by large beautifully filmed spaces and twilight lights, far from the frameworks established by the cinematographic genre. The one who kills is Anton Chigurh (coldly interpreted by Javier Bardem, who plays here one of the most surprising and bluffing roles of his career, sporting a rather incredible haircut; as for the hair styles of our dear Spanish actor, we also recommend the excellent Blow Up (Arte) on the worst looks of the latter, See it here. And the one he wants to kill is Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), an almost modern cowboy who stumbles upon two million dollars.

No Country for Old Men continues to play with the codes of the western, constantly reinventing them. The script brings out of the mouths of the characters phrases of Eastwood heroes, even if they do not suit the situation at all; the camera films Anton's violent series of murders with cold objectivity, without being too close or too distant. And strangely, this same Anton is the one who seems to have the greatest respect for death: he never kills an animal, he never speaks in the past of the dead, and he even goes so far as to keep their promises. He shares with the viewer a morbid fascination, in a silence both heavy and soothing (the Coen Brothers have chosen not to place any music in the film, surely to break once again the codes of the western where heroic music is in order). All the scenes are irretrievably linked, with short shots and impeccable photography, led by the talented Roger Deakins, Oscar-winning cinematographer recently for Blade Runner 2049.

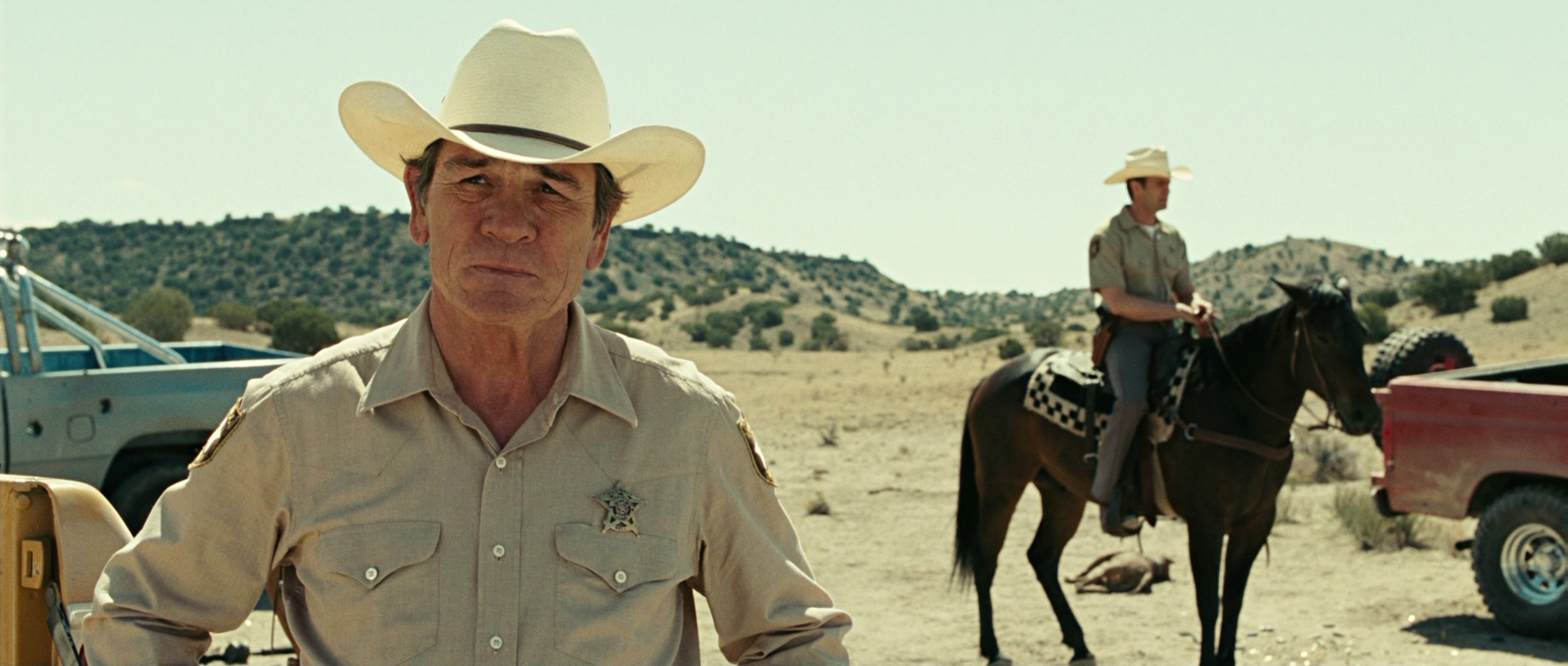

But the most important character, the one who gives the film its title, is Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a disillusioned "old man", symbol of an entire outdated era. In No Country for Old Men, the killer is no longer a bounty hunter, but the grim reaper incarnate, who does not conform to moral laws or the rules of cinema. The old sheriff can do nothing about death and is no longer respected as he should have in an old western. The shadow of the old is cut up, battered by an absurd era to which it no longer belongs.

The Coen Brothers succeed in making No Country for Old Men a more than successful adaptation, which reinvents and expands cinematic frameworks to make a simple scheme a picture full of nuances. If the genre is aging, the cinema of the Coen brothers does not take a wrinkle.