In this committed thriller, the French director attacks the giants of agrochemicals head-on. Goliath is an unbreathable film because of its breathless pace and its staging as close as possible to the characters. Among them, that of Pierre Niney, against employment as a lobbyist bastard. But wouldn't there be an air of déjà vu?

Goliath: a sharp thriller but without a real personality

An image desaturated to the extreme, sobs and a trial. From his introduction, Goliath imprints an astonishing fluidity of narrative. We will follow one of the black robes of this hearing, Patrick, a lawyer specializing in environmental cases. Her fate will cross that of France, an anti-pesticide activist, and Mathias, a lobbyist for Phytosanis, an agrochemical company. Their story will coincide via Tetrazine, a molecule used in mass agriculture and considered carcinogenic in the long term.  This political-legal thriller is Frédéric Tellier's third film. The filmmaker, first author and director for television (Un cop, Les Hommes de l'ombre), tackles a new anchored story. His first two works were already inspired by real events, first with the hunt for serial killer Guy Georges (The SK1 Affair), then by following a great burn of the Paris firefighters (Save or Perish). With Goliath, Tellier falls in love with the victims of Tetrazine and more broadly, with the state-industries that hide the dangerousness of their products behind marketing.

This political-legal thriller is Frédéric Tellier's third film. The filmmaker, first author and director for television (Un cop, Les Hommes de l'ombre), tackles a new anchored story. His first two works were already inspired by real events, first with the hunt for serial killer Guy Georges (The SK1 Affair), then by following a great burn of the Paris firefighters (Save or Perish). With Goliath, Tellier falls in love with the victims of Tetrazine and more broadly, with the state-industries that hide the dangerousness of their products behind marketing.

Racy and human

The image of Goliath is his first asset. Overexposed, as if to aggravate and sanctify her remarks, she gives a sense of magnitude to this river story spread over several months. The camera, most often harpooned to the serious faces of the characters, never seems posed, always hesitant. This shoulder filming energizes or even dynamites the sequences, allowing itself some stylistic effects in the shocking moments. Well helped by sound tessitura that oscillate towards the high-pitched, Goliath would almost distill an atmosphere of the end of the world. Hearing becoming as important as sight, to show us (with a capital m) the consequences of pesticides on human lives. With a very committed discourse, close to activism (coming from the character of Emmanuelle Bercot), Frédéric Tellier intends less to reveal the acts than the deep characters of the protagonists of the story.  Focused first on Patrick (Gilles Lellouche, very invested), the feature film will reverse the scale of value with the point of view of Mathias (Pierre Niney), brilliant lobbyist and therefore useful bastard of a capitalism out of breath. This duality becomes the heart of the film and its main strength. Far from being complacent in his denunciation, Goliath prefers to reveal an impossible struggle between two opposing forces. On the one hand, plebeian rage, symbolized by the sick, little people and the "little" militant lawyers. On the other, the industrial giant, ready to the worst baseness to impose its profitability schedule.

Focused first on Patrick (Gilles Lellouche, very invested), the feature film will reverse the scale of value with the point of view of Mathias (Pierre Niney), brilliant lobbyist and therefore useful bastard of a capitalism out of breath. This duality becomes the heart of the film and its main strength. Far from being complacent in his denunciation, Goliath prefers to reveal an impossible struggle between two opposing forces. On the one hand, plebeian rage, symbolized by the sick, little people and the "little" militant lawyers. On the other, the industrial giant, ready to the worst baseness to impose its profitability schedule.

An impossible battle

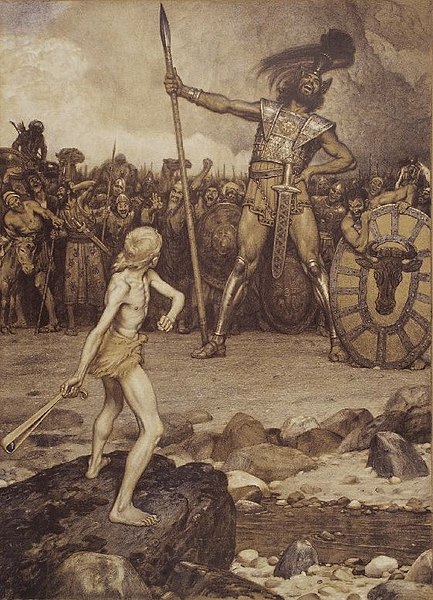

A misaligned fight that calls for another in its title: David against Goliath. In this legend, a young shepherd faces a three-meter-high Philistine. Despite the obvious inequality of the confrontation, David killed the giant with his simple slingshot, throwing stones at his forehead. The Philistines fled and David became king.  Everything, from the staging to the structure of the narrative, tends to transpose this biblical story. Frédéric Tellier will quote it directly in a passage of his film. In a meeting between lobbyists and the French state, a painting proudly appears in the background. It is actually a lithograph by Osmar Schindler dating from 1888, entitled…David and Goliath! And we would almost find the analytical key of the film in this work: monochrome, reminiscent of Zack Snyder's 300 and presenting Goliath and his allies facing a naked David, alone against all. A disturbing parallel with Frédéric Tellier's feature film, which makes the same choice of colorimetry and absurd confrontation.

Everything, from the staging to the structure of the narrative, tends to transpose this biblical story. Frédéric Tellier will quote it directly in a passage of his film. In a meeting between lobbyists and the French state, a painting proudly appears in the background. It is actually a lithograph by Osmar Schindler dating from 1888, entitled…David and Goliath! And we would almost find the analytical key of the film in this work: monochrome, reminiscent of Zack Snyder's 300 and presenting Goliath and his allies facing a naked David, alone against all. A disturbing parallel with Frédéric Tellier's feature film, which makes the same choice of colorimetry and absurd confrontation.

Already seen

In this adaptation, Goliath is not a man but a voracious system, the battlefields: offices and streets conducive to demonstrations, suits and ties replace armor and signs the slingshot. In this rhythmic struggle, Pierre Niney finds his pin with a counter-employment interpretation, perhaps not perfectly subtle, but which finally changes from his usual register.  Christine Tamalet / SINGLE MAN[/caption] Goliath still suffers from a syndrome of this subgenre of the activist thriller: that of repeating oneself. Because it ultimately inspires only its redundancy among several leading figures: The Investigation (Vincent Garenq, 2014, already with Gilles Lellouche as the headliner), Lord of War (Andrew Niccol, 2005) or Dark Waters (Todd Haynes, 2019) among the most recent. And if it prefigures among the most accomplished works, it remains a kind of photocopy in its structure. Nothing in Goliath is surprising or really makes you want to call for revolt. A denunciation certainly, but of a confounding banality in his story, which does not take any path that has not already been marked by others. In this, Goliath will not reach the pantheon, but will already appear as a solid francophone reference. A perfectly paced and intelligently conducted thriller, Goliath is worth its clear treatment of a sadly topical case. His hunting game between the giant capitalism and the tiny people proves captivating, even if it lacks bitterness, or even reasons to exist as a new militant film. It still allows a welcome lighting and great performances of committed actors. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I3gZ6Iz6yQI

Christine Tamalet / SINGLE MAN[/caption] Goliath still suffers from a syndrome of this subgenre of the activist thriller: that of repeating oneself. Because it ultimately inspires only its redundancy among several leading figures: The Investigation (Vincent Garenq, 2014, already with Gilles Lellouche as the headliner), Lord of War (Andrew Niccol, 2005) or Dark Waters (Todd Haynes, 2019) among the most recent. And if it prefigures among the most accomplished works, it remains a kind of photocopy in its structure. Nothing in Goliath is surprising or really makes you want to call for revolt. A denunciation certainly, but of a confounding banality in his story, which does not take any path that has not already been marked by others. In this, Goliath will not reach the pantheon, but will already appear as a solid francophone reference. A perfectly paced and intelligently conducted thriller, Goliath is worth its clear treatment of a sadly topical case. His hunting game between the giant capitalism and the tiny people proves captivating, even if it lacks bitterness, or even reasons to exist as a new militant film. It still allows a welcome lighting and great performances of committed actors. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I3gZ6Iz6yQI